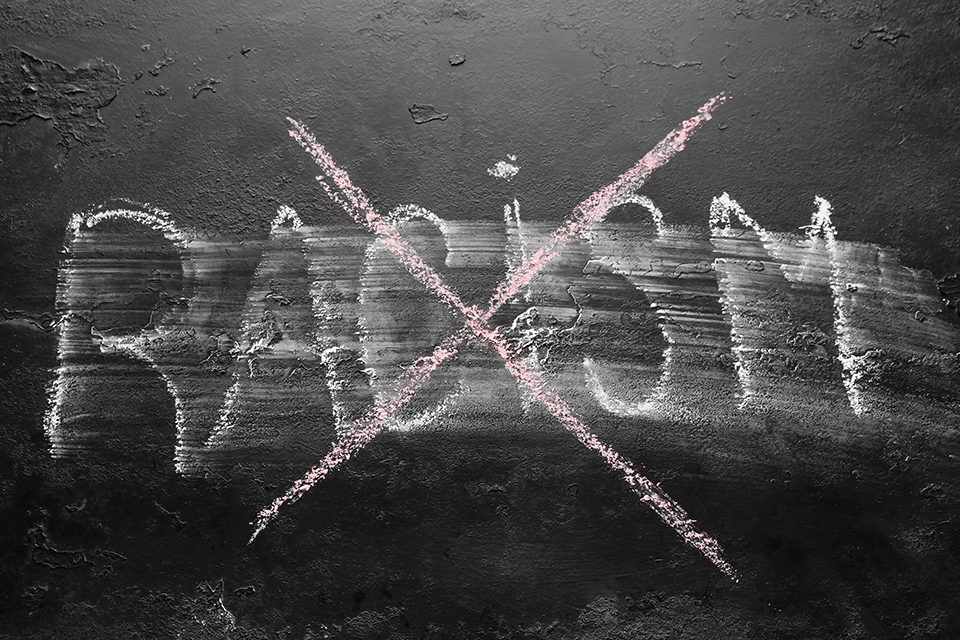

Unpacking Race and Racism in the Muslim American Community

By Jimmy E. Jones

Jan/Feb 2024

“Except his [Lut’s] wife, who we have ascertained will be of those who will lag behind.” (15:60)

The sad story of Prophet Lut’s (‘alayhi as salaam) wife appears in all of the Abrahamic scriptures. I grew up in a Black Baptist Church in Bible Belt Virginia during the 1950s and 1960s. Consequently, after I converted to Islam in the 1970s, I was reacquainted with the powerful lesson embedded in this important narrative: No matter how righteous or God-conscious your relatives are, it’s still possible for you to be so caught up in “looking back” at what displeases God that you end up “stuck” like a pillar in the problematic past.

When it comes to race relations in the Muslim American community, it seems that many African-American Muslims and their “allies” are too fixated on “looking back” at the twin American sins of slavery and segregation. Therefore, they often do not focus on the powerful positive perspective that Islam brings to this very sensitive, politically-charged issue. Consequently, many of us are so honed in on White supremacy and Black victimhood that we remain a bit stuck in a narrative that fails to move us forward. In this article, I intend to unpack both of these concepts in a way that might facilitate building a stronger, more cohesive Muslim community.

White Supremacy

Given my life as a young Black boy growing up in the legally segregated South, I knew White supremacy quite well. Us “colored” children attended underfunded schools using books and supplies cast off by our White counterparts across town. When I encountered a White person in downtown Roanoke, Va., I knew better than to obstruct their path or get too close.

In addition, the racially motivated brutal murder of Emmett Till on Aug. 28, 1955, was a terrifying reminder of what happens to young boys like me who dared to violate the prevailing racial norms. Even though I was only 9 years old at the time, the horrific Jet magazine open casket picture of Till’s brutalized 14-year-old body was traumatizing. The image was so powerful that it still impacts my interactions with White women almost 70 years later.

Such was White supremacy’s nature in a state where Whites and Blacks were jailed if they intermarried. This reality lasted up until June 12, 1967, when the U.S. Supreme Court in Loving v. Virginia banned such anti-miscegenation laws nationwide. Even though White supremacy was particularly detrimental to Black people, its negative impact also affected others.

For example, eugenics, the science of “improving the race,” became a very popular movement in the 1920s. In fact, 30+ states (led by Virginia) passed involuntary sterilization laws to rid society of “defectives” (e.g., immigrants, blind, deaf, “feeble minded”). A 1927 U.S. Supreme Court case, Buck v. Bell, involved a poor young White girl that Virginia wanted to legally sterilize. This case became a major catalyst for the eugenics movement. “Liberal” Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes famously stated in the court’s written opinion that “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

These words, and the ruling in which they were contained, led to 70,000+ forced sterilizations of the “unfit,” a practice that lasted until the 1970s. All of this was done by using the authority of various state laws. This pseudoscientific movement is meticulously documented in Edwin Black’s “The War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America’s Campaign to Create a Master Race” (Four Walls Eight Windows: 2003). Even liberal intellectual luminaries at Harvard, Yale and Stanford were ardent advocates of this “racial improvement” effort.

The point here is that while “White supremacy” was a powerful negative phenomenon for Black people, it was also used to suppress and murder others. For instance, lynching is usually associated with Black repression. However, according to The Stanford Daily initially, it was actually more frequently used in the western part of the country against Mexicans before and after the Reconstruction (stanforddaily.com, May 19, 2022).

Thus, White supremacy has always been about more than just Black and White.

Black Victimhood

Perhaps the most stunning outcome of the de jure segregation system that I endured during my formative years was that I never considered myself a victim. The people who nurtured me at home, in school and at the High Street Baptist Church that I attended never allowed me to focus on the fact that I was treated as a second-class citizen. Instead, they insisted that I strive to be the best I could be, no matter what the circumstances. Consequently, we all understood that excellence was the standard for every one of us young Black children.

This refuse-to-be-a-victim attitude is in stark contrast to that of some of the Black leaders and their “allies” in the Muslim American community today, who often portray us as primarily victims of White supremacy and immigrant interlopers who adopt White supremacist attitudes. Far too little emphasis is placed on the value that we currently add to the Muslim community and the broader American society.

Racism toward us is still a real and persistent scourge in both contexts. However, if you adopt the narrative presented by many African-American Muslim leaders and their “allies,” you would think that most Muslim “immigrants” are “anti-Black” and that most Blacks are very poor.

For a more optimistic view, consider the census data used by Eugene Robinson in his stereotype-shattering book “Disintegration: The Splintering of Black America” (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group: 2011). The data he references support the central thesis of the book’s first chapter: “Black America doesn’t live here anymore.” In the chapter, he asserts that by 2010, middle-class Black Americans had become the Black community’s largest segment. Racism is still a serious, deadly problem in this country. However, things have gotten a little better.

Facing Forward

If we Muslims want to avoid the fate of Prophet Lut’s(‘alayhi as salaam) wife, I strongly urge our community’s members to come together across ethnic boundaries in order to construct a more inclusive multicultural future for us and for all Americans by focusing on some Islamically inspired concepts that we all know quite well:

• When it comes to the Qur’an and biology, there is no such thing as “race.” As pointed out in 4:1, all humans were created from a single being and its mate. Thus, “race” is indeed a social construct.

• Even though Prophet Muhammad (salla Allahu ‘alayhi wa sallam) clearly loved his people and place of birth, he never put his cultural allegiance above the shahada, which encourages Muslims to be in one mutually supportive community.

• A binary approach to solving the country’s racial issues (e.g., “You are either a racist or an anti-racist,” as per the currently popular author Ibram X. Kendi in his bestselling book “How to be an Antiracist”) will lead to even more racial animus. We should heed the lessons in the oft-quoted 49:13, that we are created as nations and tribes as a test of whether we can get to know one another.

• As witnesses for all humanity (2:143), Muslims are obliged to step up and have tough conversations around race that will lead to healing, rather than to increased bitterness and blaming (see Harlan Dalton’s “Racial Healing” [Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group: 1996] for an excellent discussion of how this might happen).

We should all take time to learn about the complex history of race relations in this country through books like Matthew Frye Jacobson’s “Whiteness of a Different Color” (Harvard University Press, 1999) or videos like the excellent three-part PBS series “Race: The Power of an Illusion” (2003).

Further, as a Muslim African American, I believe that we are better off if we focus on the value we bring to a situation, as opposed to acting like “victims” who need to be protected from “micro-aggressions” and be given “safe spaces.” Black victimhood is not the best response to White supremacy.

Jimmy E. Jones, DMin, is executive vice-president and professor of comparative religion and culture at The Islamic Seminary of America, Richardson, Texas.

Tell us what you thought by joining our Facebook community. You can also send comments and story pitches to horizons@isna.net. Islamic Horizons does not publish unsolicited material.