The real Dracula was a sadistic warlord

Misbahuddin Mirza

January/February 2022

Bram Stoker could never have imagined that his 1897 Gothic horror novel “Dracula” would continue to be such a record-breaking bestseller even after more than a century. His novel also made its main protagonist, the demonic Count Dracula, the world’s most famous fictional vampire.

Stoker’s book, still a bestseller after 124 years, has been adapted numerous times as movies, TV series and other forms of broadcasting. To keep the audience interested and engaged, movie producers have kept modifying Dracula’s character while claiming to remain true to the original character.

However, it appears that this all changed after Prof. Radu Florescu, the Romanian-born historian and director of Boston University’s Eastern European Research Center co-authored with Raymond T. McNally the famous “In Search of Dracula” (1972). By linking the fictional Count Dracula to the 15th-century Romanian warlord Vlad the Impaler, they caused movie producers to make dramatic changes to Dracula’s character. They romanticized him, changing him from the original repulsive and repugnant monster to a debonair gentleman and then finally, keeping up with the latest trend, threw Islamophobia into the mix.

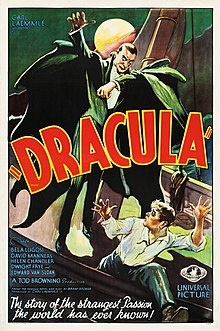

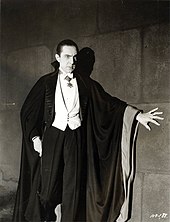

The Dracula of later movie adaptations bears little if any resemblance to Stoker’s 1897 Dracula. Sarah L. Peters’ paper “Repulsive to Romantic: The Evolution of Bram Stoker’s Dracula” describes how Dracula’s character kept changing in each movie reincarnation. To make her point, she cites three movies that claim to be based directly on Stoker’s novel: German director F. W. Murnau’s 1922 silent film “Nosferatu: Eine Symphonie des Grauens,” and two American films, Tod Browning’s “Dracula” (1931) and Francis Ford Coppola’s “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” (1992).

“Stoker’s Dracula is pure evil, repulsive and terrifying. He needs to take life, to end it or pervert it, and his foes are those who wish to preserve life. The roles in the story are rigid and clear-cut with definite lines between good and evil, echoing the Victorian ‘concern for purity, for the reduction of ambiguity and the preservation of boundaries’” (Spencer, Kathleen L. “Purity and Danger: Dracula, The Urban Gothic, and the Late Victorian

Degeneracy Crisis.” English Literary History 59.1 (1992): 197-226. 203). Like the band of men determined to destroy him, the reader has no sympathy for the monster that destroys lives without remorse. In an entry of her journal, Mina says, “I suppose anyone ought to pity anything so hunted as is the Count. That is just it: this Thing is not human — not even beast. To read Dr Seward’s account of poor Lucy’s death, and what followed, is enough to dry up the springs of pity in one’s heart” (Stoker, Bram. Dracula. The Essential Dracula. Raymond McNally and Radu Florescu. New York: Mayflower, 1979. 35-277. 186).

By linking the fictional Count Dracula to the 15th-century Romanian warlord Vlad the Impaler, they caused movie producers to make dramatic changes to Dracula’s character. They romanticized him, changing him from the original repulsive and repugnant monster to a debonair gentleman and then finally, keeping up with the latest trend, threw Islamophobia into the mix.

Forty-one years before Florescu’s book was published, Tod Browning’s “Dracula” came up with a variation that removed much of the hideous, animalistic quality so important to the count’s previous versions. While no love story is involved, Count Dracula was now presented as an attractive, sophisticated aristocrat who moves about easily in polite society. Yet, “Both of these earlier Draculas had to move at night, hiding in shadows, while sleeping in coffins throughout the day, never making casual contact with humans beyond the meeting with Harker in Dracula’s own home. However, any sympathy the viewer may have for Browning’s Dracula based on his attractive looks is soon replaced by revulsion at Dracula’s bloodthirstiness (Corbin, Carol, and Robert A. Campbell. “Postmodern Iconography and Perspective in Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula.” Journal of Popular Film and Television, 27.2 (Summer 1999): 40-49).

Ninety-five years after Stoker’s book was released, and 22 years after Florescu’s book linking Dracula to Vlad the Impaler, Coppola takes Dracula’s character to a completely different level. “In an extended prologue to the film Bram Stoker’s Dracula, however, Coppola presents an origin that refers to Vlad Dracul, or Vlad the Impaler, the historical figure to which Dracula’s legend is attributed (Corbin and Campbell. 49).

Dracula is seen as a fearless warrior who joins the Crusades to defend Christianity, praying for the protection of his beloved wife Elisabetha while he is gone. After defeating the Turks and impaling his enemies on long spikes, Vlad returns to discover that Elisabetha has killed herself after hearing the false news of his death. Enraged, he renounces God and pledges his life to the devil. Dracula’s motivation throughout the film is the pursuit of his lost love, reincarnated in Mina Harker, and the traditional theme of the pursuit of blood is subordinated.

“The vulnerable, loving character of Coppola’s Dracula stirs the viewer’s sympathy more than previous versions. The vile, untouchable creature has become the tragic demon lover. Dracula’s death, then, is not a victory for the good force that has rid the earth of a terrible evil; it is, instead, an act of love by Mina’s hand (similar to Nosferatu, but a contrast to Stoker’s and Browning’s Draculas who are killed by men protecting Mina) that released the soul of the damned lover so that he may rest peacefully.”

Gary Shore’s 2014 movie “Dracula Untold” goes a step further and adds the Islamophobia element to keep up with today’s climate of hate. Vlad the Impaler’s character is humanized, and he is shown as making a massive sacrifice by becoming a demon (i.e., Dracula) to protect his subjects and kingdom from the Ottoman sultan.

The true story of Vlad Tepes Dracula, or Vlad the Impaler, differs from the one portrayed in the Coppola and Shore movies. Vlad II Dracul was the ruler (Voivode) of Wallachia, a principality south of Transylvania. He was granted the surname “Dracul” (Dragon) upon his induction into the Order of the Dragon — a Christian military order sustained by the Holy Roman emperor. He had four sons, including Vlad Tepes, who would go on to become Vlad the Impaler — the progenitor of the Dracula vampire myth. The neighbouring Kingdom of Hungary overthrew Vlad II. So, Vlad II sought the Ottoman sultan’s help to regain his Wallachian throne and willingly offered two of his sons, Vlad Tepes Dracula (Vlad III) and Radu cel Frumos (Radu the handsome), to be raised by the sultan as collateral.

The sultan sent an army to fight off Vlad II’s enemies and reinstall him on the Wallachian throne. Vlad III and Radu were sent to learn the Quran, literature, logic, Turkish and Persian. Radu soon became a friend of Sultan Murad II’s son Mehmed II, the future conqueror of Constantinople. Radu, later known as Radu Bey, became a brilliant general and served in several battles, including the one that captured Constantinople.

In 1447 John Hunyadi, regent-governor of Hungary, invaded Wallachia and killed Vlad II. Mircea, Vlad II’s elder son was tortured, blinded and buried alive. The sultan’s army went back and installed Vlad III on Wallachia’s throne. Is it possible that the way his father and brother were tortured and killed caused Vlad III to turn into the vicious psychopathic mass murderer that he later became?

Vlad III the Impaler soon turned on the Ottoman armies that had installed him on Wallachia’s throne. Having been raised among Muslims, he spoke Turkish fluently and was intimately familiar with the empire’s war techniques. His soldiers dressed in Ottoman uniforms during guerilla operations. He killed indiscriminately — men, women, children, Turks and Bulgarians. In one incident he impaled 23,884 Turks and Bulgarians.

History.com states, “As the ruler of Walachia (now part of Romania), Vlad Tepes became notorious for the brutal tactics he employed against his enemies, including torture, mutilation and mass murder. Though he didn’t shy away from disembowelment, decapitation or boiling alive, his preferred method was impalement, or driving a wooden stake through their bodies and leaving them to die of exposure. During his campaign against Ottoman invaders in 1462, Vlad reportedly had as many as 20,000 victims impaled on the banks of the Danube.” The total number of his victims numbered over 80,000.

In response to this brutality, Sultan Mehmed II personally marched to Wallachia and installed Radu Bey as its new ruler. Vlad Tepes the Impaler fled to Hungary. The sultan ordered Radu Bey to pursue his evil brother to stamp out this heinous depravity from the face of this planet. Vlad the Impaler was killed, and his head was sent to the Sultan, where it hung from the gates of Constantinople for about three months as a deterrence to the world’s wicked.

Elest Ali, in his New Statesman’s movie review of “Dracula Untold,” succinctly concludes: “Today, vilification of Islam has reached such heights, that even when the Sultan is cast opposite history’s bloodiest-psycho-tyrant, it’s Dracula who emerges as the tragic hero.”

Misbahuddin Mirza, M.S., P.E., is a licensed professional engineer, registered in the States of New York and New Jersey, who served as the regional quality control engineer for the New York State Department of Transportation’s New York City Region. He is the author of the iBook “Illustrated Muslim Travel Guide to Jerusalem.” He has written for major U.S. and Indian publications.