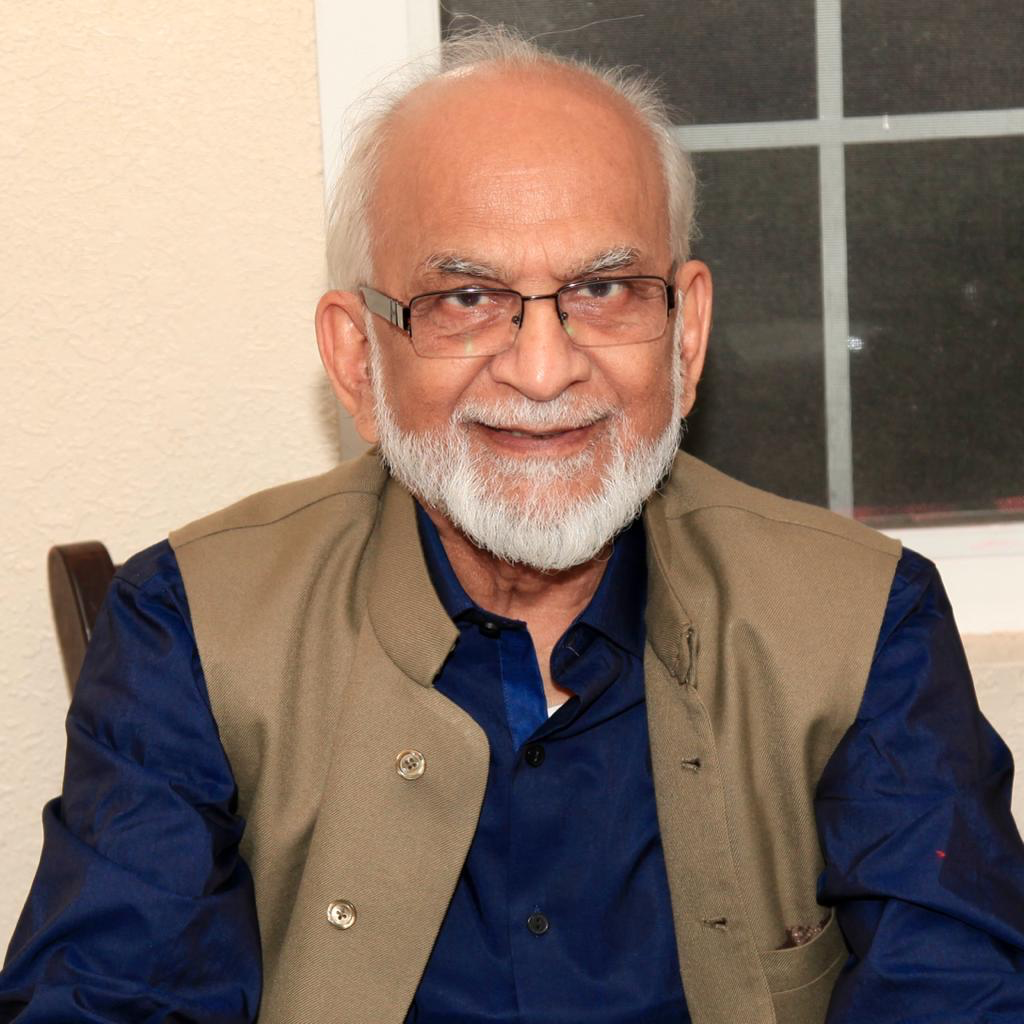

The Father of Modern Islamic Banking (1932-2022)

By Aslam Abdullah

January/February 2023

Dr. Muhammad Nejatullah Siddiqi, who left behind an astounding legacy, lived the life of an ordinary person. He was the embodiment of humility, and yet his works proudly display his mastery of the subjects he wrote on. Thousands benefitted from his expertise and scholarship, yet he was like a teenager while sitting with his children and grandchildren, enjoying every moment of their company.

Born in the small Indian town of Gorakhpur in 1931, on Nov.18, 2022, hundreds of scholars and leaders across the globe assembled through Zoom to pay tribute to this giant of a leader not only in economics, but also in the worldwide Islamic movement. This father of modern Islamic banking’s legacy will enable millions of the deprived to secure a dignified existence. He left this world on November 11 in San Jose, Calif., having spent his adult life enabling countless poor people to access interest-free loans to achieve their dreams.

Nejat means salvation, and his work brought salvation to people who could not advance their financial growth due to their lack of capital. Who would have thought that young Nejat, growing up in colonial India, would one day teach in two of the world’s most prestigious universities: India’s Aligarh Muslim University and Saudi Arabia’s King Abdul Aziz University? Indeed, India colonial officials were reluctant to help hard-working aspiring students translate concepts into institutions that might one day be able to launch and finance thousands of development projects worldwide.

Laboring hard to pioneer an economics based on the divinely eternal principles of justice and equity, he authored 63 significant books, published hundreds of articles and gave thousands of lectures worldwide.

His most widely read book is “Banking Without Interest,” which was published in 30+ editions between 1973 and 2022. His other English-language works include “Islam’s View on Property” (1969), “Recent Theories of Profit: A Critical Examination” (1971), “Economic Enterprise in Islam” (1972), “Muslim Economic Thinking” (1981), “Banking Without Interest (1983)”, “Issues in Islamic Banking: Selected Papers” (1983), “Partnership and Profit-sharing in Islamic Law” (1985), “Insurance in an Islamic Economy” (1985), “Teaching Economics in Islamic Perspective” (1996), “Role of State in Islamic Economy” (1996) and “Dialogue in Islamic Economics” (2002).

He received two major awards: the King Faisal International Prize for Service to Islamic Studies (1982) and the Shah Waliullah Award for his contribution to Islamic Economics (2003).

Describing the future of Islamic economics, in 2013 he wrote that the changing world would call for five strategic changes in approach: • The family, rather than the market, is the starting point in economic analysis • Cooperation plays a significant role in the economy, complementing competition • Debts play a subsidiary rather than the dominant role in financial markets • Interest and interest-bearing instruments play no part in money creation and monetary management and purpose-based thinking supplants analogical reasoning in Islamic economic jurisprudence.

Reaching these conclusions involved spending sleepless nights to absorb every significant book on economics and finance he could lay his hands on while simultaneously interacting with divine guidance. In the passage below, he describes this journey:

“I have been involved in Islamic economics most of my life. At school, however, I studied science subjects but switched to economics, Arabic, and English literature for my BA degree at Aligarh Muslim University, which I joined in 1949.

“My reading habit influenced my decision. I was devoted to al-Hilal and al-Balagh magazines, published under Maulana Abul Kalam Azad (1888-1958), poet, critic, thinker, and one of the great leaders of the Independence Movement. I also read al-Tableegh and was influenced by the Deobandi scholar Maulana Ashraf Ali Thanawi (1863-1943), the author of the famous book on belief and correct conduct (for women), Heavenly Ornaments.

“And as most young people of my age and time, I studied the works of Maulana Abul Ala Maududi (1903-79). Two of Maududi’s pieces deeply impacted me: lectures at Nadwatul Ulama, Lucknow, and a scheme he proposed to Aligarh Muslim University, both in the mid-1940s, later published in a collection titled Taleemat. Under the influence of these ulama – religious scholars — I abandoned science and the engineering career I had planned. Instead, I wanted to learn Arabic, gain direct access to Islamic sources, and discover how modern life and Islamic teachings interacted. I stuck to this mission, even though I had to take several detours stretching over six years — to Sanwi (secondary) Darsgah e Jamaat e Islami, Rampur, and Madrasatul Islah in Saraimir before I arrived eventually at Aligarh to earn a Ph.D. in economics.

“The years spent in Rampur and Saraimir were full of lively interaction with Ulama. We spent most of our time discussing the Qur’an, the traditions of the Prophet, commentaries on the Qur’an, fiqh (jurisprudence), and Usul-e-Fiqh, or principles of jurisprudence. That this happened in the company of young men my age, fired by the same zeal, was an added advantage. We had each chosen a subject ii political science, philosophy, economics — that we thought would enhance our understanding of modern life. We combined modern secular and old-religious learning to produce something that would right what was wrong with the world. We received a warm welcome from Zakir Hussain (1897-1969), the former President of India, then Vice-Chancellor of Aligarh Muslim University; Mohammad Aaqil Saheb, Professor of Economics at Jamia Milliyah Islamia, Delhi; and by eminent teachers at Osmania University in Hyderabad.

“Our mission was to introduce Islamic ideas to economics. These were at three levels:

- A background provided by Islam’s worldview places economic matters in a holistic framework, a set of goals for individual behavior and monetary policy, [and] norms and values should lead to appropriate institutions.

“Maududi argued that this exercise performed in critical social sciences would pave the way for progress toward an ‘Islamic society.

“I believed in the idea. I was aware of the extraordinary times through which Islam and Muslims were passing worldwide. Islam was ‘re-emerging’ after three centuries of colonization, preceded by another three centuries of stagnation and intellectual atrophy. The great depression had just exposed capitalism’s darker side, and Russian-sponsored socialism was enlisting sympathizers. We thought divine guidance, as introduced by Islam, had a chance, provided the case was convincing.”

He worked hard to develop a convincing case for Islam via three monumental contributions to giving the Islamic movement a new shape and direction: delving deep into theology to change the paradigm of thinking, concretizing concepts into institutions to improve the social economy and introducing objectivity into the polity.

Siddiqi devoted a book to the Sharia’s objectives (maqasid al-Shari‘a). Disagreeing with al-Ghazali’s five categories of objectives, he suggested there were many additional goals, among them humanity’s honor and dignity , fundamental freedom, justice and equity, poverty alleviation, sustenance for all, social equality, bridging the rich–poor gap, peace and security, preserving of system and cooperation at the world level. He supported his stand with Quranic verses and Hadith, especially in dealing with non-Muslims.

To him, the concept of the Sharia’s objectives has existed from the very beginning of Islamic history. Al-Juwayni (d.1085) was the first one to use the term, and his disciple al-Ghazali (d.1111) divided it into five categories: the protection of religion, life, reason, progeny, and property. Ibn Taymiyah (d.1328) replaced progeny with the protection of dignity and argued that these objectives shouldn’t be limited to protecting people from the forbidden, but should also include securing their benefits. Thus, the number of objectives has no limit.

Ibn al-Qayyim (d.1350), following his teacher Ibn Taymiyah (d.1328), included justice among the objectives. He examined the opinions of al-Shatibi (d.1389) and Shah Wali Allah al-Dihlawi (d.1763), and conducted a quick survey of the contemporary literature.

Theology

Siddiqi challenged the prevailing notion that poverty is a divine blessing and that Islam has little to do with physical resources, because the life of the hereafter was far more important. Instead, he argued that material resources are open for those who explore the universe and that inequality and injustice will prevail if the world ignores the rules based on divine principles. He urged Muslims to follow the Quran, which states that creation exists for humanity’s betterment and benefit. He also rejected the theological premise that the material world belongs to non-Muslims and the world to come to the Muslims, and strongly contended that Muslims will achieve their proper spiritual dimensions only when they begin exploring the universe.

Social Economy

Siddiqi believed that marginalized and poor people should have equal opportunities to improve their lives. He argued that their ability to access capital will enable them to somehow grow financially and bring about meaningful change in their families. He labored hard to concretize the rules of the usury-free lending system and urged financial institutions to develop a mechanism to uplift marginalized people by making resources available in a non-exploitative manner. Today, 2,600+ financial institutions practice usury-free banking systems in the organized sector and thousands more in the unorganized sector. Millions of Muslims have benefitted.

Polity

Siddiqi strongly advocated for an egalitarian, classless society. However, this idea is meaningless if only certain classes have access to financial resources. Restructuring the economy to serve and uplift society’s weakest sections will cause social engineering to fail. He referred to the Quran’s proclamation that creation’s physical resources are for everyone. Classes will cease to exist only when the social structure ensures everyone’s dignity. Pride will come only when everyone has autonomy and access to the tools needed to improve their living conditions. He described the current capitalism-based system as brutal and a significant obstacle to real economic growth.

Having reached the age of 91 when he breathed his last surrounded by his life-long wife and children, Siddiqi’s legacy has ensured him a perpetual reward. Due to his work, there are now 500+ Islamic banks and thousands of other non-interest-bearing financial institutions. His nephew Dr. Ahmadullah Siddiq (professor, media studies, Illinois) said, “It is not a loss of a family, but a loss of a generation that always looked at Uncle Nejatullah as a shining source of inspiration.”

Contributed by Aslam Abdullah, editor-in-chief of Muslim Media Network Inc., publishers of “the Muslim Observer” and the resident scholar at Islamicity.com.

Tell us what you thought by joining our Facebook community. You can also send comments and story pitches to horizons@isna.net. Islamic Horizons does not publish unsolicited material.