A minority within a minority: Francophone Muslim Canadians are as diverse as Islam itself

By Zaineb Survery

January/February 2023

Prophet Muhammad (salla Allahu ‘alayhi wa sallam) said, “Indeed, God created Adam from a handful of collected earth; thus, the children of Adam are also of the earth. Some are (of shades) red, white, or black and whatever is amongst them is of the ease, difficult, evil, and good” (“Sahih al-Tirmidhi,” 2955).

Islamic Horizons (Sept./Oct. 2022, p. 58) included an article entitled “Learning the Languages of the Land” on the need to become bi- or multilingual. In the North American context, this means learning Indigenous languages, Spanish or French. Such knowledge can help us progress professionally, improve societal values and increase other people’s understanding of Islam.

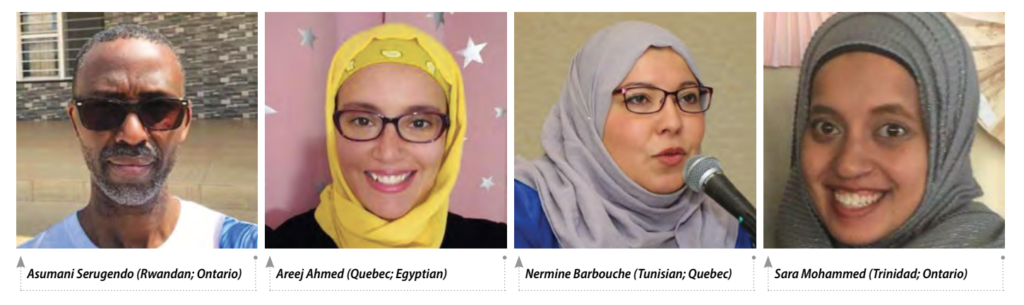

Specifically, Canadian Muslims need to learn French, their country’s co-official language. At the same time, this enables more French-speaking Canadian Muslims to become civically engaged, which can help deter the nationwide anti-Muslim xenophobia and fill the large gap in French-language Islamic literature for children. This article offers glimpses of eight Francophone Muslims and the challenges they face.

Coming from all walks of cultural, professional and provincial life, they are are diverse as Islam itself. Muslims welcome and work around linguistic differences by speaking a common language. However, their most important shared traits are remaining resilient and proud Muslims while being civically engaged in a bilingual society.

New Brunswick: Cheikhou Moctar Drame

Cheikhou Moctar Drame, a French-speaker who hails from Senegal, lives in the coastal city of Moncton. He has lived in Canada for nearly a decade, working in the telecommunications sector, co-founding an import/export company and serving as the Moncton Muslim Association’s vice president. French is the official language of New Brunswick, which has the largest Francophone population — over 30% — outside Quebec. This demographic is higher in the interior and the regions bordering Quebec. However, English’s influence is stronger, which can be a significant challenge.

Moctar says, “French doesn’t pass with most of the population; it’s truly a minority language. Private services require us to speak English. It’s difficult when you can’t or don’t want to speak English.” In fact, his primary form of correspondence for this article was French, for he “wants to understand and be understood. In English, for the moment, this isn’t the case.” He continues to outline that he “wants an Islamic education for [his children], which is currently absent. The environment doesn’t offer Islamic values.”

English-based Islamic education required three generations to be firmly planted in North America, with organizations such as ISNA, the Muslim Children of North America (MCNA) and the Muslim Association of Canada (MAC) leading the effort. Right now, the only French-based MAC school is in Quebec. Francophone Muslims in New Brunswick are a minority; for now, their children’s education is family-driven.

Quebec: Nermine Barbouch, Omemah and Areej Ahmed

Nermine Barbouch, who has lived in Montreal for 30+ years, graduated in French literature. She is conversational in French and Spanish and understands German, Italian and Russian. Originally from Tunisia, she grew up with French as her second language. She leads the Forum Musulman Canadien (Canadian Muslim Forum), which collectively voices Muslims rights in Quebec; is a case worker at Sakeena Homes, a women’s shelter; and an interpreter at the Montreal Children’s Hospital.

Barbouch is in the thick of xenophobia, given her various working roles. She openly admits many Euro-Quebecers consider that Muslims ignorant and uneducated and are surprised to hear a visibly Muslim individual speaking French. She argues that Quebecers need to realize the challenges faced by refugee families from a war-imposed country: learning a new language, dealing with significant trauma, raising a child(ren) with physical challenges and struggling financially with rising city costs and a limited income.

Unfortunately, Canada is currently racism-galore, be it via legislative bills or subtle interactions. However, sometimes an industry is bureaucratically exempt due to the limited supply-and-demand of professionals. One such field is healthcare.

Omemah (last name), a hijab-wearing clinical nurse born and raised in Laval, Quebec, has Pakistani roots. She talks with her patients in French, English or Urdu. For her dialysis-assisted patients, aged 19 to 90 years old, her hijab is likely the least of their worries. Rather, occasionally an elderly patient feels at ease in warmly “considering her a Quebecer” for speaking in French with them. In fact, the only times she has experienced racist attitudes in Quebec was while working in retail customer service during her teens. She would speak to customers on the phone in French, only to hear the same customer in-person saying they want “to speak to the white girl they spoke to on the phone.” She would politely reply with, “That’s me.”

Currently, Canada faces a countrywide nurse shortage due to Covid burnout — and Quebec is being severely affected. Its xenophobic and politically France-inspired laïcité law, Bill 21, outlines who gets to work in the public eye while wearing a “religious symbol.” Essentially, this depends on who hands over the pay check, is a glamorous or intensive decision-making role or if the job market is already saturated.

For example, according to Bill 21 (schedule 3, section 7, clause 10), physicians, judges and public school teachers working in Quebec cannot wear the hijab, whereas those working for the government as a nurse (health care is “free” here) or in IT can. This bureaucratic cherry-picking gets awfully confusing even for the Québecor. One tries not to take Bill 21 personally, challenging as that is for Muslims. In the meantime, IT offers Muslim Francophones opportunities in Quebec.

The Quebec government is currently hiring 3,000 French-speaking overseas IT workers (Montreal Gazette, April 2022). Incidentally, Areej Ahmed is pursuing IT in Montreal, having moved there from Egypt with her family over seven years ago. She is currently learning French. Her husband, who learned it in an Egyptian primary school, quickly found work as a data architect. But he feels that French, as an industrial language, is dying. The perk: Quebec pays one to learn the language! Provincial Bills 96 and 101 have been pivotal in pressuring private businesses to operate officially in French.

However, that is a significant pressure on the typical older adult recent migrant. Ahmed notes of her French classmates, aged between 18 to 60: “Few succeeded (in the older age) … many became fed up; went to Arab stores, restaurants or bakeries to look for jobs and forgot about the language.” Thus this demographic hasn’t progressed either financially and/or intellectually.

Barbouch noted the same problem a generation earlier. As a high schooler in Montreal, her immigrant friends were dragged out of class by their immigrant parents who refused to or could not learn French and used the child as a translator. She states, “The older generation does whatever possible to not speak French, resulting in some of my friends not getting past a high school education” and thus being stuck in labor-based work. Currently, as Muslim communities have no internal organizational leadership to bridge this gap, the onus is on the youth to forgo higher education.

Ontario: Anonymous Afghan man, Sara Mohammed, Asumani Serugendo and Sumra

Muslims outside Quebec are also pursuing French. Among them are an Afghan man choosing to remain anonymous and Sara Mohammed. This man, an Ontario resident since his youth, earned a Teaching French as a Second/Foreign Language certificate (Université Laval, Quebec). Since 2012, his various public service roles have helped him progress professionally in Toronto.

Also living near Toronto is Sara Mohammed, who has a Trinidad and Tobago background. Neither of her parents speak French; yet she graduated with honors in French linguistics from the University of Toronto, attends teachers’ college and has been a visible Muslim teacher in the Ontario public school system for over 12 years.

Currently, Ontario has a major shortage of French teachers because its government has reduced French’s cultural (and political) impact by reducing the French immersion school curriculum from 90% to 50%. In the long-run, this decision is very unhealthy for Ontarians and even more so for Muslims here, who are already caught in the crossfire, given Canada’s linguistic polarization.

Yet some seek to make the best of such difficulties. Cosmopolitanism, comfort and community appear to have led Asumani Serugendo and his family to live in English-dominant Toronto for the last 15 years, despite French being their mother tongue and their Rwandan roots. They moved to Toronto mainly due to the supportive network of friends.

Serugendo, whose nutrition experience in Rwanada was dismissed, is a nutrition manager acquiring Canadian credentials. He says that given the competitiveness, the Ontario government’s bilingual opportunities aren’t an option, for hardly 5% of Ontario jobs require such a skill.

Pairing his children’s quality education with the Muslim community’s lifestyle is a blessing. His children attend French immersion school. Living in Thorncliffe, Toronto’s most Muslim-oriented region, he has access to indoor prayer congregations in his building complex. French is not a lost cause for him for his family, for “it’s good to know any other language. French is safe, being another international language used by UN. With 300 million French speakers in the world, a global perspective is good.”

International experiences cannot be devalued, a fact that the Canadian mentality still needs to realize. Having lived in France as a youth for two years, Sumra pursued French at the university level after returning to Pakistan and participated in an exchange program to Paris. Within a year of moving to Canada, she acquired a bilingual HR consultant role at a major Canadian financial institution in Toronto, where she has now worked for seven years.

Such a pace of professional success is unheard of for many immigrants — even Anglophones. She (re)learned French on her own via movies, friends and on the job, such as starting at the United Way as a bilingual fundraiser. Occasionally she has to deal with the shock her new Euro-centric colleagues or clients display when hearing her converse in French.

Ultimately, Islam teaches us to not limit ourselves or others to stereotypes. Who are we to judge another’s challenges? We must increase our empathy toward our Francophone co-religionists and be willing to learn other languages. Overall, we should at least try to offer a greater understanding of Islam.

As Moctar stated (in French), “We obviously try to deal with the negative things [while living in a predominantly English-speaking country] by looking for alternatives. The positive experiences are always well-lived, and that makes us overcome the negative ones.” Central to Islam is recognizing the blessings all around us. And so finding positivity in a challenging society, regardless of language, is the only way forward.

Zaineb Survery, a Canada-based community writer and educator, is the founder of Indigenous and Muslim Education (IME) and a freelance writer on Indigenous history and social inequality.

Tell us what you thought by joining our Facebook community. You can also send comments and story pitches to horizons@isna.net. Islamic Horizons does not publish unsolicited material.