Lessons from a minority within a minority for present Muslims in the West

By Zaineb Survery

January/February 2023

History is not everyone’s cup of tea. Yet, it does provide lessons for a contemporary society to progress. At the same time, it also offers guidelines as to what choices resulted in a society’s downfall.

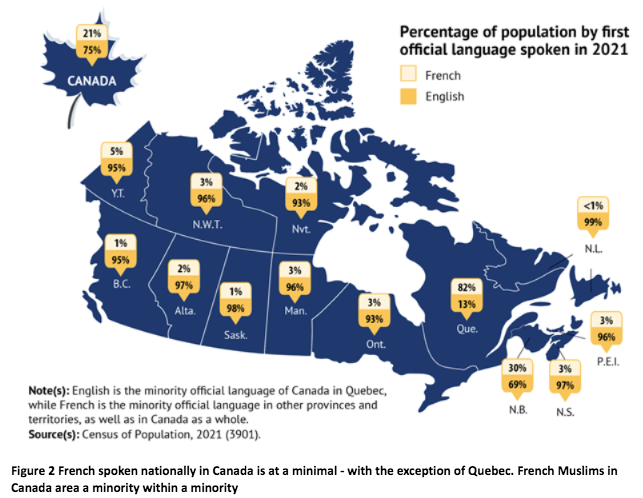

The history of Canada’s Francophone Muslims offers vital lessons to our current and challenging times. Muslims in the West face many barriers to integrate within mainstream society due to language, faith, religion and overall mindset. Frankly, these Muslims are parallel to Muslims overall: The percentage of primary French speakers in Canada’s provinces, outside of Quebec, is 1-3%, whereas Muslims represent only 1% of the country’s population — a minority within a minority.

Their influence, however, is nationwide. The timeline can be divided into three main parts, as per the main mode of transportation available: ship/boat (the 1600s to the late 1800s), railroad (the late 1800s to the 1950s) or plane (the 1960s and onward). In other words, primarily during the Trans-Atlantic slave period, the building and expansion of the Trans Canada railway and the airlines.

Each period provides information, varying from wholly negative to positive, to Francophone Muslims’ residence in Canada and is vital to contemporary Muslims overall in the West.

Period 1. Islam didn’t survive among the enslaved Muslims arriving in Canada because of the forced separation and breakdown of families imposed by the early colonizers who moved to the Maritimes. Currently, Muslims in the West are facing a breakdown of their own: family members separating due to technology overload.

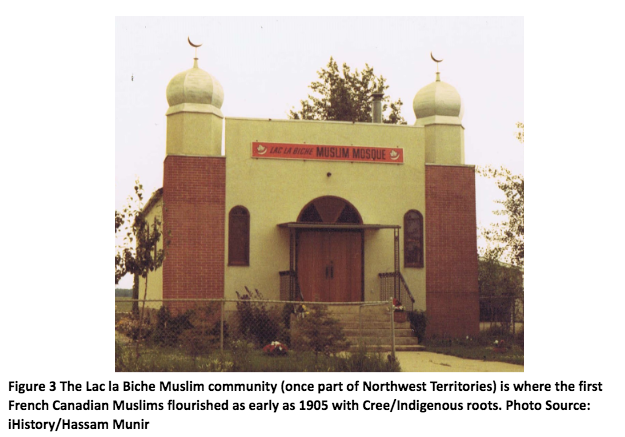

Period 2. Islam was established in Canada during the 1890s to the 1950s among those who were resilient enough to earn an independent living (owning businesses) amidst significant racist hurdles and times, parents using limited resources to teach children their faith, cultural intermarriage and community collaboration regardless of large rural land distances. Their effects live on this day: The al Rashid Mosque in Edmonton, Alberta, has operated since the 1930s, and the Lac le Biche Muslim community, originally part of the North West Territories, has been active since the 1940s.

Period 3. The Islam that most of us relate to, spurred from the 1960s onward, is now found in the heaviest Muslim-populated provinces of Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia, thanks to the modern aviation industry. This era’s positive points: Muslims from various cultural backgrounds collaborate together, earn professional livelihoods and establish the “Muslim identity” by building mosques, creating a political presence through legislation, as well as by acquiring professional recognition via governmental employment. Sadly, there are also negative points: disunity and a lack of understanding/cooperating due to differences in schools of thought, contrary to the Hadith literature.

Muslim Francophones

The Slave Trade Era. Nationally, Canada has yet to officially (via government) and socially (by mainstream) acknowledge that it took part in slavery. According to Government of Canada, Cultural Heritage, almost 4,000 slaves were forcibly transported to the country from 1629 to 1834. Globally, however, 1 in 3 slaves who survived the Middle Passage were Muslim, according to scholar and historian Dr. Abdullah Hakim Quick (see Deeper Roots; 2007). That means, more than likely, that 1,200 Muslims would have been living in Canada.

Unfortunately, there are no existing indications (yet) as to how many of them spoke French. However, the first recorded slave who landed in Canada was 6-year-old French-speaker named Olivier le Jeune from Madagascar; his original name is unknown. Madagascar had been exposed to Muslim Arab and Indian traders 600 years earlier. Islam left a residual influence there, given that 5% of the country’s population is still Muslim.

The question remains: Why didn’t Islam survive among these 1,200 Muslims’ descendants? Say Olivier was Muslim. How much about Islam and its practices could he have known, given the forced early separation from his parents? Multiply that with other young Muslim children arriving as slaves. Similarly, adult slaves were also separated from their children when the latter were still young. Thus, knowledge transmission became impossible.

In our current times, the greatest threat facing Muslims in the West is the parent–child communication divide due to technology overload. The Muslim family system is evaporating steadily due to parents being more swamped in their daily livelihood and financial stresses, while youth acquire the attention and social acceptance from peers who are unknowingly negatively influenced from social media platforms. Ultimately, the foundational pillars of Islam to understand the Quran, maintain social ties and helping the vulnerable is being lost within our youths.

The Railway Era. Surprisingly, Canada’s earliest Muslim immigrants settled in prairie lands. The Hudson Bay’s interconnected river systems and resulting fertile lands allowed the Indigenous Peoples to settle in what is now Winnipeg, Manitoba, centuries before being displaced by European settlers during the 1800s. As a result, Indigenous Peoples found alternate means of living more in the northwest: the fur trade. Enter Muslim entrepreneurs.

The earliest Muslim immigrants came from the Levant — modern-day Lebanon, Syria and Palestine. French culture was a significant influence in Levantine culture, particularly Lebanon. In fact, the French-created term Levant means “lever” or “to rise,” — a reference to the East and the rising of the Sun.

The strongest Muslim Francophone connection during this era didn’t come from the young male Lebanese migrants, but by their marrying into the Métis Indigenous Peoples.

Indigenous Peoples within the prairies/Rockies stem from a Métis background — a mix of Indigenous (e.g., Cree or Ojibway) and Europeans (including the French, the original fur traders) and their offspring. As a result, the Cree language contained French words and phrases — just enough to break the ice between the Lebanese male trade-post owners and Indigenous populations looking to buy their goods. The two groups eventually established strong sociopolitical ties.

Lac le Biche, in what was then part of Northwestern Territories but is now in northern Alberta, is to this day a stronghold of committed Muslims who have both an Indigenous and Lebanese/Syrian lineage.

What enabled this Francophone Muslim–Indigenous community to thrive for over a century? Culture, tradition, family and monotheism. They have shown great persistence in upholding community collaboration ties and keeping their youth grounded in Islam, both of which have enabled them to be part of the mainstream. In fact, one Lac le Biche resident — defenseman Ismail Abougouche — is part of the Kelowna Rockets, a major hockey league team. A community truly worth having coffee with!

The Flying-In Era. Quebec has set the precedent for both Francophone and other Muslims to participate in the Canadian political system. Irrespective of cultural and ethnic backgrounds, the growing city members cooperated effectively and thereby paved the life of ease we enjoy today. The community’s longest lasting contribution was getting a private member’s Bill — Bill 194 — approved by the Quebec Legislature in 1965 that recognized Islam as a minority religion. Before then, births had to be registered and marriages had to be held at the province’s churches.

We now take our nikahs for granted, attending marriages that have been registered at a mosque or through an imam. Imagine if we still had to get married in a church, under the Trinity. Imagine the spiritual misery and thinking about how we could even begin to break away from such a system? This creativity, unification and persistence of letting go of the ego and power grab, even of a small masjid, needs to be enacted by each of us for Muslims in the West to truly succeed in spreading Islam.

By and by, contemporary Muslims of all ages can acquire vital lessons if we take the time to study how the sacrifices of earlier Muslims engendered the life of ease that we have today as Muslims in the West by acquiring selfless bold ambitions to serve the mainstream at large, by being open-minded and persistent in learning French (Canada) or Spanish (the U.S.). Family disunity, which threatens Islam’s spread in the West, must be counteracted by having meals together and turning off smartphones to acquiring anger management and communication skills, as well as spending more one-on-one time with our children. Cultural intermarriages need to be more broadly considered by tunnel-vision families, and prejudices need to be tossed aside and replaced by the deen as the primary influence in our lives.

French Muslims in Canada teach almost four hundred years’ worth of lessons in practicing Islam today due to legislative and socially amalgamative ease, but also potentially destructive if we do not forgo our differences. We need to significantly reprioritize and instill the Prophetic tradition where real unity is maintained despite our differences if we truly want to pass Islam on to the next generations.

Zaineb Survery, a Canada-based community writer and educator, is the founder of Indigenous and Muslim Education (IME) and a freelance writer on Indigenous history and social inequality.

Tell us what you thought by joining our Facebook community. You can also send comments and story pitches to horizons@isna.net. Islamic Horizons does not publish unsolicited material.