Dr. Nagamia’s Quranic Collection and Priceless Quranic Manuscripts Are Now on Display

By Rabiyah Syed

Nov/Dec 2024

It may come as a surprise that Rolling Meadows, a Chicago suburb and home of the Nagamia Institute of Islamic Medicine and Science (NIIMS), houses a museum of rare copies of the Quran. This initiative springs from founder Dr. Husain Fakhruddin Nagamia’s love of the Quran.

Nagamia, who served as chief emeritus cardiovascular thoracic and cardiac transplant surgery at Tampa General Hospital, wore many hats during his career: past president of the Islamic Medical Association of North America (IMANA); member of the ISNA Founder’s Committee; founder and chairman, the International Institute of Islamic Medicine; and a founding member of the American Federation of Muslims of Indian Origin (AMFI), which seeks to achieve 100% literacy and universal education for India’s minorities.

NIIMS was founded as the International Institute of Islamic Medicine in 1992, a branch of IMANA. In 2019 it became NIIMS and dedicated itself to researching the history of Islamic medicine. As an avid historian, he took many trips and held conferences both here and abroad to share and spread Islamic medicine’s legacy and history.

The Nagamia Institute of Islamic Medicine and Science

Alia Hirzalla, NIIMS’ executive director, conducted an informative tour of the branch’s origins.

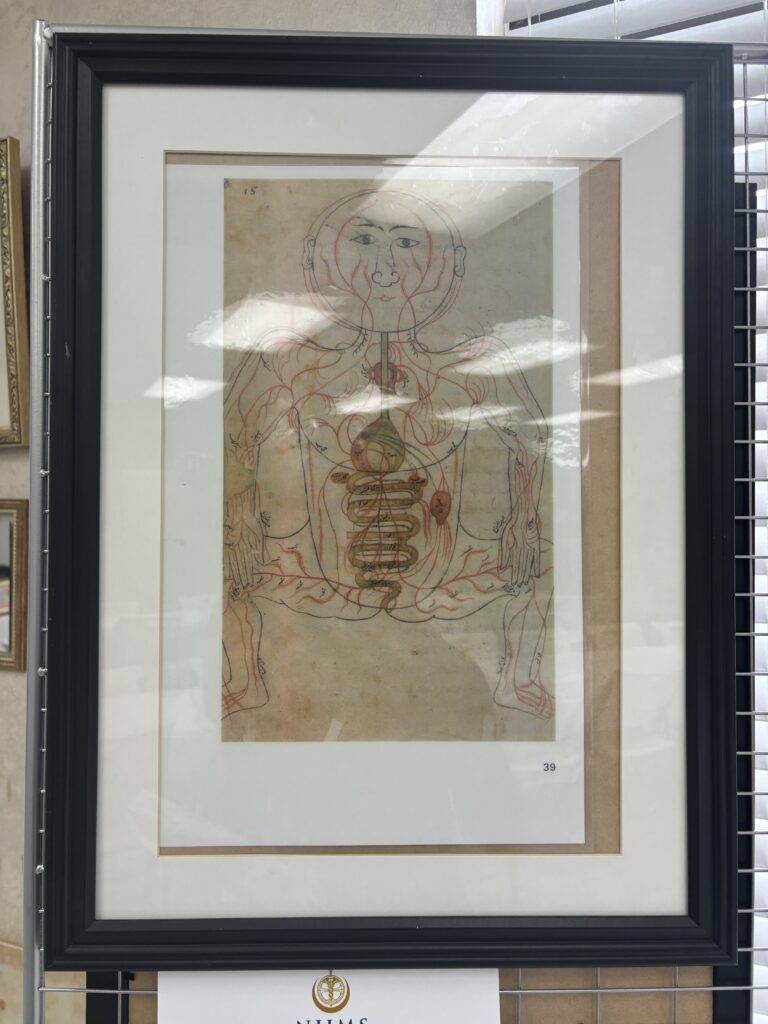

She states that Muslims have been instrumental in both scientific and medical discoveries and developments. NIIMS is displaying historical drawings from Muslim scientists depicting the human body (pictured below). A great deal of research has gone into documenting their contributions. Many of Nagamia’s lectures and workshops, all given to educate people about Islamic science, have been uploaded to its website.

A large amount of research and information compiled under Nagamia’s supervision has been released in Mahmood A. Hai and Mubin Syed’s “The Contributions of Islamic Civilization to Medicine” (2023). Hirzalla remarks, “[With the book we hope to] show how Muslims contribute to history.”

NIIMS also has other gems to offer: a library full of new and old books on many subjects, as well as calligraphy classes in which individuals and groups can participate. “With all this effort, this is our goal: to help people know more about us and learn about Islam,” Hirzalla said.

As part of that mission, a special place was created – the Quran Museum, a hidden gem nestled in this complex.

The Quran Museum

The Quran Museum, an extended branch of NIIMS, is located in a building donated by Nagamia. Unfortunately, he passed away before its opening.

The museum, beautifully designed by Illinois-based Turkish architect Suheyb Kayacan, displays many well-preserved Qurans, some dating as far back as the 1600s, from around the world. Many were acquired and donated by Naim Dam (founder and CEO, Hema-Q Inc.), whose medical startup has curated these artifacts from auctions worldwide for the past 30 years.

All of these incredibly interesting artifacts help paint an image of Islam’s past, more specifically a historical chronology of how the Quran was inscribed over time.

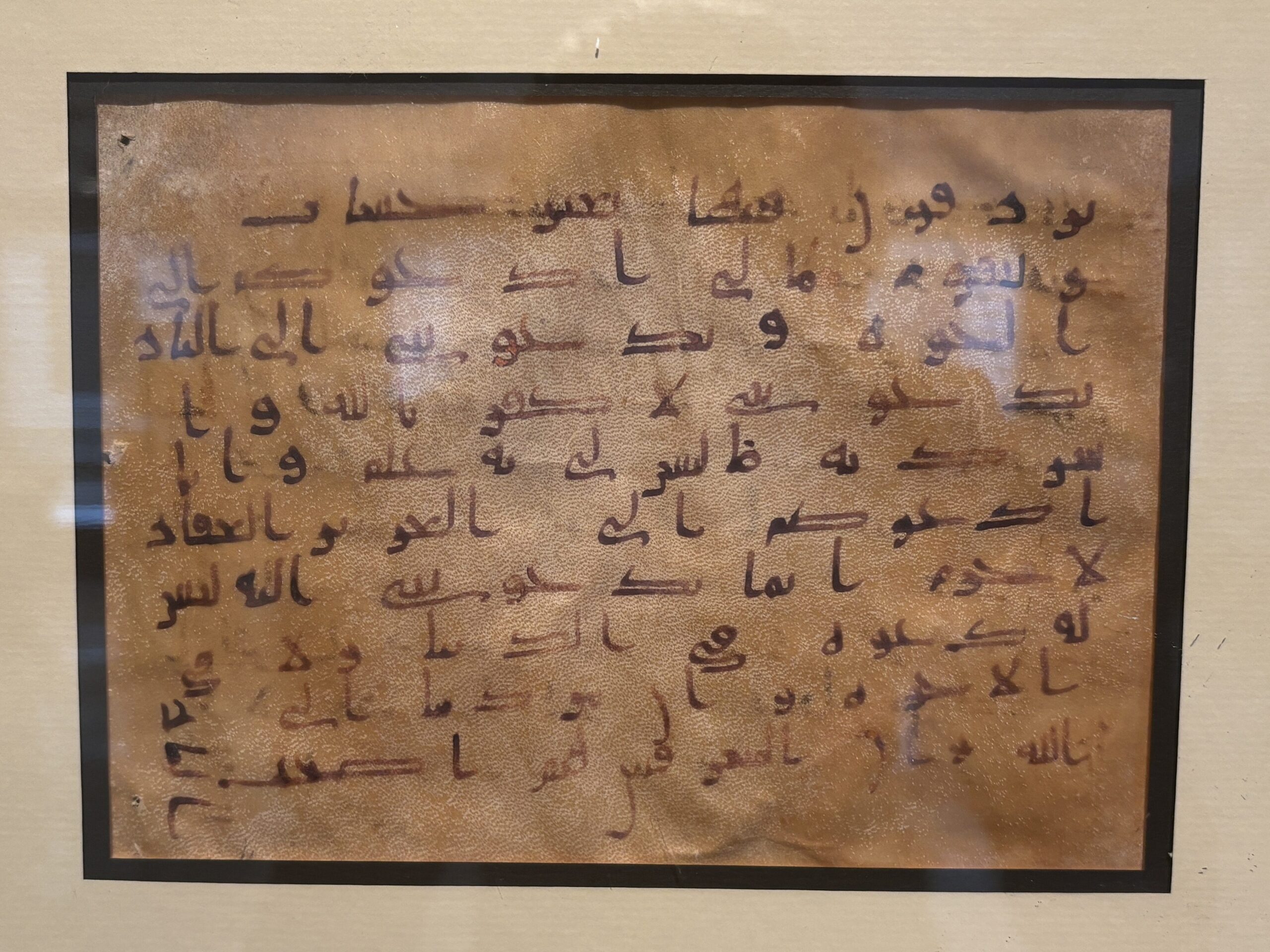

The tour highlights the importance of how and why the Quran was put into written script. Hirzalla, explaining its history of preservation, states that this was initially done via memorization in the hearts and minds of the Prophet’s (salla Allahu ‘alayhi wa sallam) Companions. Some of its text was written on animal skins and other materials. Later on, specifically during Caliph Abu Bakr’s riddah wars (632-33) against rebellious Arabian tribes, some of which were led by rival prophet claimants and led to the martyrdom of many Companions. Abu Bakr entrusted Zayd ibn Thabit with compiling the complete Quran.

This copy remained with the caliphs until Caliph Uthman ibn ‘Affan entrusted various Companions with transcribing and sending copies of it to all Muslim lands. After that, he standardized the text and ensured that there were no wrongful recitations by ordering all stray compilations to be burnt.

Hirzalla points out that “400 languages have already died. For example, hieroglyphics, the Egyptian writing, can be read in our language… but no one knows how it used to be pronounced [or read before].” This, she explains, is why the Quran was written down in its original Arabic form: to prevent mistakes due to Arabic becoming a lost language and to make it easier for non-native Arabic speakers to read it.

One displayed piece is from when the Quran was first written without harakat (diacritical marks). “This piece was written in [Kufic script]. An Arabic speaker can read it very easily… but other people [that haven’t learned or grown up with the language] cannot. It’s gonna be hard for them. They may misread it,” she says.

The next piece was from the time of Caliph Ali ibn Abu Talib. She relates how Abu al-Aswad ad-Du’ali (d.688) – one of the earliest, if not the earliest, Arab grammarians – at first refused but finally agreed to revise and add the harakat. She explained that the Quran’s whole meaning changes when its verses are read incorrectly. Upon realizing this after seeing two people reading the same verse differently, he agreed to do so.

“He took his students and told them to put [a red dot when he made different sounds. For example] when he made the ‘ah’ sound, the students were to put a dot on top of the letter,” Hirzalla explained. Other sounds, including the ‘e’ and the ‘o’ received a red dot underneath and next to the letter respectively. Al-Khalil ibn Ahmad al-Farahidi (718-86) replaced the red dots [with specific diacritics called harakat].

Interestingly, what makes these pieces more exquisite is the use of gold and saffron as writing embellishment material. “All these pieces are handwritten. If you see anything gold, it is pure gold. Anything you see in red [the red dots on the paintings] are in saffron, and that’s why they are still vibrant in color till now,” she said. As you move through the tour, you begin to see the evolution of the Quran’s script into the style that we have today.

When these items were purchased and donated, NIIMS brought experts to test them to help date and gather more information on each one. Experts examined the type of paper, the material used (such as different ink and gold), and the writing style to help identify when they were written and their geographical origin.

Among the displayed manuscripts is one from 16th-17th century China. Interestingly, when this copy was inspected, it smelled of smoke, as if it had been in a fire, indicating that it was most likely saved from burning. Other exquisite artifacts include the first translated Quran from the late 1700s.

With such rare and old objects, special precautions must be taken to help preserve them. The room has to be specially cleaned and kept at a certain temperature. In addition, regular room lights must be turned off and special lights used to illuminate the room.

The museum offers group tours and holds a calligraphy workshop. It offers much insight into a part of Islamic history that people don’t always hear about. Everyone should visit this hidden gem.

Rabiyah Syed, a senior at Naperville Central High School, loves photography and hopes to join the medical field in college.