An Exclusive Interview with Hamza Perez

By Wendy Diaz

Sep/Oct 2024

The groundbreaking documentary film “New Muslim Cool,” produced by PBS, debuted in 2009 and offered a glimpse into the lives of Hamza and Suleiman Perez, two Puerto Rican American brothers who embraced Islam during the late 1990s. Fifteen years after the film’s release, the brothers, particularly Hamza, have evolved from youth to influential community leaders.

Nevertheless, a non-Muslim audience who comes across it through streaming services such as Amazon Prime would never know about Hamza Perez’s growth beyond the film. Even if a curious spectator scans the internet for more information, news articles, video clips and academic papers focus mostly on his life in 2009. “New Muslim Cool” continues to be used as an educational tool in classrooms worldwide. However, his post-documentary growth and impact on his local community deserves more recognition.

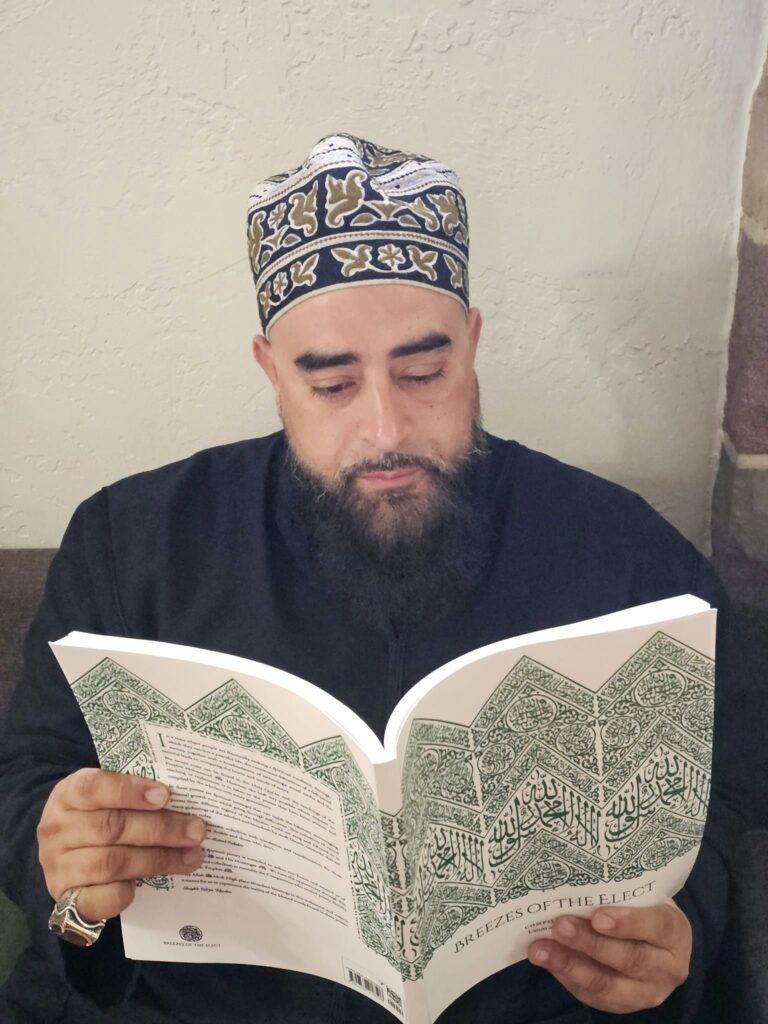

Cradling his newborn grandson in a Facebook post, the grinning Hamza looks vastly different from his depiction as one of the infamous Mujahideen or M-Team duo performing revolutionary hip-hop vocals while wielding machetes portrayed in the documentary. He sports a gray pinstriped thobe, a burgundy velvet fez hat and noticeable traces of henna color the tips of his salt and pepper beard. Although visibly more mature, his demeanor remains vibrant and youthful.

“‘New Muslim Cool’ was released in about 2009, but we really started filming in 2004, so that is a 20-year stretch. A lot has changed,” Perez said. Indeed, plenty has changed for Latin American Muslims in the U.S., whose visibility has steadily increased since 9/11. A Pew Research Center demographic portrait of Muslim Americans from 2011 reported that 6% of U.S. Muslims identified as either Latino or Hispanic. In 2022, the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding’s (ISPU) American Muslim Poll found that 9% of the approximately 3.5 million Muslims in the U.S. are Latino — approximately 315,000. As more Latinos convert or are born into Islam, Muslims who converted in the late 1990s and early 2000s are aging into new roles.

“New Muslim Cool” followed the Perez family as they settled in Pittsburgh and navigated the intersections of Puerto Rican urban culture and new Muslim identities. During filming, Perez got married, had his third child with then-wife Rafiah and the FBI raided the Light of Age/North Side Mosque, which he helped co-found.

Perez has since divorced and remarried in 2011, and is now the father to a total of eleven children. He recently became a grandfather after his eldest son Ismail, who appears in the documentary, started a family of his own.

Giving Up Music

Shortly after the film’s international success, he stopped performing and left the music industry to focus more on religious studies. His mother, who seemed to show concern and even disapproval for Perez’s decision to abandon his Christian upbringing, converted, along with his father, grandparents and other extended family members. Perez traveled to West Africa to study Islam, received certifications in religious sciences and became an imam. He attributes his personal growth to the study of Prophet Muhammad (salla Allahu ‘alayhi wa sallam).

Although the audience sees a dedicated Perez beginning to study and even teach Islam to the inmates at his local prison in “New Muslim Cool,” he was still in the initial stages of his conversion. He moves from Massachusetts to Pittsburgh to start a new life with his family. The post-9/11 atmosphere of suspicion presents a series of hurdles to his professional and spiritual growth. His career as an outspoken rapper and songwriter calling for revolution and rebellion haunts him as he begins working in the prison system as a chaplain.

Perez begins studying Islam in depth at the local mosque and attempts to distance himself from some of his songs’ contentious lyrics. These initial stages of his evolution are portrayed in the documentary film, but the audience is left with a half-hearted portrayal of the Latino convert experience.

He believes that the Muslim experience for Americans in general, and for Latino Muslims in particular, differs from that of foreign-born Muslims. He now feels like he’s more connected to his Islamic identity than his culture after having been Muslim for over a quarter of a century.

More Than Conversion

Media coverage and academia often focus on the “phenomenon” of new conversions and ignore the presence of decades-old converts as well as second- and third-generation Latino Muslim families. Harold Morales, author of “Latino and Muslim in America: Race, Religion, and the Making of a New Minority” (Oxford University Press, 2018) said, “There is so much more to Latino Muslims than conversion, yet this is the most dominant emphasis in news stories on Latino Muslims. The myopic focus on conversion is evident through a quick reading of headlines.”

Converts like Perez and his family, who accepted Islam a few years prior to or after 9/11, have now been Muslim for over two decades. And yet they rarely receive any attention from the news or academia on how their roles have changed.

“I’m very respectful of my family’s culture, and I teach certain aspects of it that are good, but I don’t compromise on the aspects of it that are haram and toxic,” Perez said. “Islam is everything to me, and it is way more important to me than being Puerto Rican.” He cautions against prioritizing cultural heritage over Islamic principles. Emphasizing Islam’s core importance in his life, Perez urges fellow Latino Muslims to uphold its teachings above all else and not to compromise religious beliefs for cultural acceptance.

Perhaps motivated by Latino Muslim resonance with Islamic Spain, he encourages them to study works like “Ash Shifa” (Diwan Press; 7th ed., 2010; trans. Aisha Bewley), written by Andalusian scholar Qadi Iyad ibn Musa al-Yahsubi (d.1149-50), to deepen their understanding of Islamic principles and prophetic manners. Perez envisions a transformative potential if Latino Muslim leaders prioritize spiritual purification and sincere intention above all.

Shortly after the release of “New Muslim Cool,” Perez was permanently barred from the jail in which he interacted with inmates as a Muslim chaplain. However, his outreach work did not end there. For over two decades, he has been instrumental in pioneering initiatives to uplift children, particularly those from Pittsburgh’s low-income neighborhoods. His work as the coordinator of BOOTUP (Building Our Own Technology, Uplifting People) and establishing the Ya-Ne Youth Alliance for Networking and Empowerment at the Islamic Center of Pittsburgh highlight his dedication to empowering youth through education and mentorship.

When a young Perez detached himself from music completely after “New Muslim Cool,” he cited concerns for his spirituality. Surprisingly, M-Team’s controversial Clash of Civilizations album is still available on platforms like Spotify. However, this former M-Team member is far removed from the militant lyrics from 2005. Twenty years later, his primary focus is community building, social welfare and peaceful dialogue.

In an April 14 Facebook post, Perez wrote, “Our community consists of 98 percent converts who have dedicated their lives to helping spread and teach Islam.” Attached to his post was a crowdfunding drive for Masjid Anisa, the “First ever ‘Built from The Ground Up’” mosque in Pittsburgh, home to many reverts or converts.

A closer, unbiased exploration of Latino Muslims’ lives reveals that they are indeed more than their conversion stories. A decade and a half after the documentary graced the screens, Perez has transitioned from a seemingly overzealous and admittedly “ignorant” youth to an indispensable leader and mentor to hundreds of fellow Muslims and non-Muslims, both Latino and non-Latino.

The story of Hamza Perez reflects a broader trend within both the Gen X and Millennial Latino Muslim communities. Across these generations, numerous converts have emerged as influential figures, assuming roles as imams, educators, advocates and social servants.

Echoing the words of Morales, “The new generation will read about the historical and cultural links between Latino ethnicity and Islamic religion from websites and social media and from journalists and scholars. They will be a new kind of Latino Muslim, one whose central narrative will lie beyond the scope of conversion.”

By leveraging their unique backgrounds and experiences, Gen X and Millennial Latin American leaders are shaping the present landscape and laying the groundwork for a vibrant and more inclusive Muslim American community.

Wendy Díaz is a Puerto Rican Muslim writer, poet, translator, and children’s book author. She is the Spanish content coordinator for ICNA-WhyIslam. She is also the co-founder of Hablamos Islam, a nonprofit organization that produces educational resources about Islam in the Spanish language.