The Louis Round Wilson Library has a gem of special significance to Muslim Americans

Ambrotype photograph of Omar ibn Said (The Ambrotype Collection in the North Carolina Collection’s Photographic Archives)

Emily Jack

January/February 2022

The University of North Carolina’s (UNC) acquisition is contributing to scholars’ understanding of the life of Omar ibn Said, a 19th-century enslaved Islamic scholar. Kidnapped from West Africa and enslaved in North Carolina, he was renowned for his Arabic writings.

The 1856 manuscript, addressed by Said to his enslaver James Owen, contains an Islamic blessing and two Biblical texts: Psalm 51 and the Lord’s Prayer.

Eighteen examples of similar documents written by Said are currently known. According to John Blythe (assistant curator, the North Carolina Collection), this item is the first one to come to light in many years. The library has digitized the manuscript, now part of the North Carolina Collection at the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, and shared it online.

The document includes notations by other people who have handled it. According to Carl Ernst (William R. Kenan Jr., distinguished professor of religious studies, UNC-Chapel Hill), one of them appears to be Gen. George McClellan, who later became famous as a Union general during the Civil War. McClellan may have been given the document at a hot springs resort that the Owen family visited.

The manuscript “shows the way in which religion and racism were deeply intertwined in the slavery institution in America,” says Ernst, co-author of a book about Said titled “I Cannot Write My Life”). Understanding the document and the context of its creation requires knowing something about Said’s life.

Who was Omar ibn Said?

The biographical details of Omar ibn Said’s life are somewhat fragmentary, says Ernst, although he left behind a slim autobiography and was covered by newspapers during his lifetime.

Scholars agree that Said studied Islam for 25 years in seminaries in what is now Senegal. According to Ernst, Said’s writings reveal an intimate familiarity with Arabic poetry, Islamic theological literature, law, grammar and other subjects.

Said was kidnapped, shipped across the Atlantic and sold into slavery in 1807. He ended up enslaved by Owen, an eastern North Carolina politician and plantation owner.

But other facts of his life have been distorted by the historical record. Contemporary newspaper accounts handed down a narrative that scholars now reject: Said had no desire to return to Africa, was content with his enslaved status and had converted to Christianity.

The Biblical passages Said rendered in Arabic were once proffered as evidence of his conversion.

According to Ernst, “This narrative was designed as a defence of slavery. It is false. We know that in his very first document that he wrote in 1819 he asks to return to Africa. And the repeated statement that he never wanted to do so is obviously false. So, what we are faced with is a situation where people wanted to take over the story of his life and use it for the defence of slavery.”

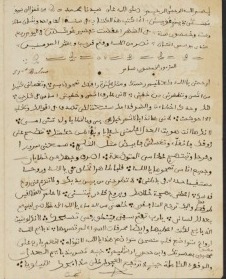

A cropped image of one page of the document.

Text, meaning and “the limits of the archive”

How should modern readers interpret this manuscript, which contains theological passages from two religions?

Ernst theorizes that the Owen family often asked Said to write a Biblical text in Arabic as a curiosity for other members of the Southern elite. Said would oblige, sometimes including a Quranic text, possibly unbeknownst to his English-speaking company.

Yasmine Flodin-Ali, a graduate student at UNC-Chapel Hill who studies race and Islam in the U.S., says these documents provoke questions: “Did Omar directly tell someone, hey, this is X, Y, Z? Or did people not really care what he was saying and just choose to interpret the documents as they wanted to?”

Said was one of a few known enslaved Muslims from Africa who left documents. However, “ultimately it’s impossible to know” what percent of the enslaved population in the U.S. were Muslim, says Flodin-Ali. “The fact is that their complex histories and backgrounds were not of interest to slave owners.”

Flodin-Ali points out that nearly all the records related to enslaved people survived because they were preserved by their enslavers. As a result, our picture of their lives is incomplete. “There’s all this work that was written directly by [Said], so trying to analyze that and think about what are the limits of the archive, what can the archive tell us, has been really exciting.”

Part of our history

The newly acquired manuscript adds to the number of texts Omar quotes in his writings, thereby opening new avenues for scholarly analysis. But the document also holds lessons for non-specialists for several reasons, according to Ernst. For one, it illustrates the presence of Islam as a religion and Arabic as a language in the American South in the earliest part of American history.

Said’s relationship with a prominent North Carolina family is also noteworthy: Owen’s brother John was a North Carolina governor and a UNC trustee for 20 years.

And locally, Said’s story is part of our history, says Flodin-Ali. “It’s so direct. He’s in Fayetteville, he’s in Wilmington in parts of his life.”

Said in the collections and beyond

This document joins other materials related to Omar ibn Said in the Louis Round Wilson Library, including two photographs of him. Some of these materials were loaned to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2017 for its “Slavery and Freedom” exhibition. A guide created by North Carolina research and instruction librarian Sarah Carrier points to Said-related materials in the Louis Round Wilson Library, as well as those in other libraries.

Taken together, the materials “broaden our picture of enslaved individuals,” says Blythe.

[Editor’s note: * Reprinted (with edits) with permission of The University Libraries, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.]