A Basic Knowledge of the Arabic Language Helps with Understanding Faith

By Carissa Lamkahouan

Nov/Dec 2024

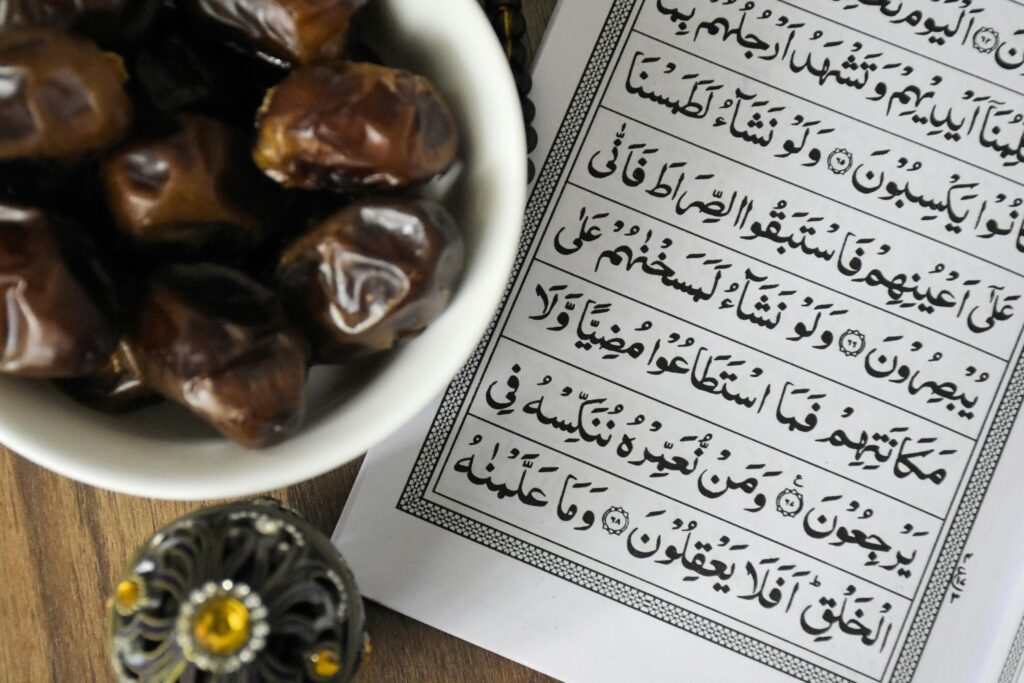

The Arabic language is, of course, intimately intertwined with Islam since the Quran was revealed to Prophet Muhammad (salla Allahu ‘alayhi wa sallam) in Arabic.

Muslims offer their five daily prayers in Arabic as well as many of the supplications they recite when leaving the home, beginning and ending a meal, or before going to sleep. Additionally, all of Islamic knowledge of the Prophet’s sunnah and authentic hadiths is in Arabic. Memorizing the Quran in Arabic, with proper pronunciation, is a goal for scores of Muslims and a source of blessing in both this life and the hereafter.

With so much emphasis on speaking and understanding Arabic, it’s no wonder that many non-Arabic speakers, including first- or second-generation Muslim Americans or converts, might feel unsure about the quality of their everyday practice of Islam. They may even wonder if they’re receiving the full benefits of their prayers and duas if they occasionally bungle the Arabic pronunciation or sometimes use their native tongue to communicate with God.

Consequently, many non-Arabic-speaking Muslims strive to learn the language, at least to the extent that they can understand what they’re saying in prayer or when they recite Quran, even if only when reading the shortest of verses.

Muslim Parents Are Putting in the Effort

This also may be a goal for Muslim parents who speak Arabic but, because they are raising their children in the U.S., have found them lacking in the language, particularly when it comes to reading, writing and understanding the text.

To remedy the situation, they may enroll their children or themselves in a weekend or full-time a Islamic schools, online or in-person Quranic academies, or in sessions with private tutors.

Hafsa Saad is one such tutor. Based in Pakistan, this married mother of one works as an online private Quranic teacher for English speakers of all ages. She has 13 years of experience teaching many students, including those in the U.S.

“I am teaching a lot of kids in America,” she said. “Many of them start in their early years and, masha’ Allah, they are learning more quickly than the adults.”

As a non-native Arabic speaker herself, she said she understands firsthand the desire to learn and to understand the language. She explained the reasons to pursue this education go beyond the everyday practice of Islam.

“We love the Prophet so much. He spoke in Arabic and Allah taught him in Arabic, so we want to speak it too,” she said. “When I say things in my own language (Urdu), it sounds different (than how it’s meant in Arabic) and it makes it hard to relate to. Saying certain things in Arabic, like Bismillah, makes my practice better and deepens my connection with Allah.”

That desire to relate to and connect deeply with Islam is, Saad believes, why so many Muslim parents seek out Arabic and Quranic teachers for their children, especially those growing up in non-Muslim countries where Arabic is not the mother tongue. Those parents can’t rely on Islamic studies and Arabic being taught in school, and many fear their children lose out on crucial lessons as a result. This situation may be especially tough for those parents who enjoyed and benefited from that type of childhood education.

Mosques Play Their Part

To fill in the gaps, many mosques around the U.S. offer after-hours or weekend Islamic-language lessons and/or Quran classes. Full-time private Islamic schools have popped up as well, with many earning full accreditation, including the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools and the Council of Islamic Schools in North America (ISLA).

According to ISLA’s 2021 data, approximately 300 Islamic schools operate in the U.S. and are educating 50,000+ students. There also are a smattering of Islamic colleges, including Islamic American University (Michigan), Zaytuna College (California) and the American Islamic College (Illinois).

Sabiha Gire has experienced non-Arabic-speaking Muslims’ need for language lessons as a community liaison Houston’s Al-Noor Mosque. She said the mosque serves a large immigrant population, including people from Afghanistan, Ethiopia, as well as India and Pakistan.

Gire said that in addition to trying to acclimate themselves to the U.S., many immigrants have taken advantage of the mosque’s weekend and after-school religious and Arabic-language programs, which are available to children and adults alike. She said that about 80 students attend Sunday school there, while about 20 parents take adult classes. The weekday sessions draw another 25 children, “mostly from our immigrant community.”

Muslim American converts can face the same challenge as non-Arabic-speaking Muslims. Because they don’t read, write, or speak the language, it makes it that much harder to ensure that their children will.

Ryan Siddiq, a convert from Connecticut raising two children, has felt that struggle. With no multi-generational Islamic knowledge to pass on to her children, she and her husband chose full-time Islamic school for their son and daughter. She said the choice was important, despite the high price of private school.

“I wanted them to grow up learning what Arabic they could and learning Islamic manners,” she said.

For Siddiq’s children, the learning has been slow but steady, with them learning how to pray in Arabic and memorizing several surahs. However, they do not speak Arabic fluently and, with no Arabic skills of her own, Siddiq worries how much of the language will stick as they grow older.

Saad said she understands that even when people take advantage of Arabic-learning resources at their school or local mosque, instilling Arabic into non-native speakers living in an English-speaking country is no easy task.

In these cases, Saad recommended focusing efforts on learning and perfecting the Arabic of the five prayers and important duas first, but also listening to Quranic recitations for the serenity it can bring to the heart and mind. The Quran, when read and recited in melodic Arabic, can be a source of calm, peace and inspiration for its listeners.

For those who are set on reciting in Arabic themselves, Saad encourages reading from a transliteration, even if you have less-than-perfect pronunciation. “The Quran is a miraculous book, so we have to read it, even if we don’t understand it, so that we may get the blessing,” she said. The Quran, read via translation in one’s own language, can also be an excellent way to connect with the faith.

Carissa Lamkahouan is a freelance journalist based in Houston. Her work has appeared in newspapers and magazines locally and internationally, including AboutIslam.net, The Houston Chronicle, Inventors Digest, WhyIslam.org, Animal Wellness and The Muslim Observer.