Secular and Islamic approaches to health issues don’t always provide the same answers

Meriem Benlamri’s infographic, based on Sobia Faisal-Ali’s research (Chelby Daigle, The Muslim Link)

Amber Khan

January/February 2022

Learning about health is especially important for youth. Therefore, most public schools require such a class in order to address common youth-based topics like puberty, bullying, relationships, suicide, intoxicants, sexuality, body image, hygiene and fitness.

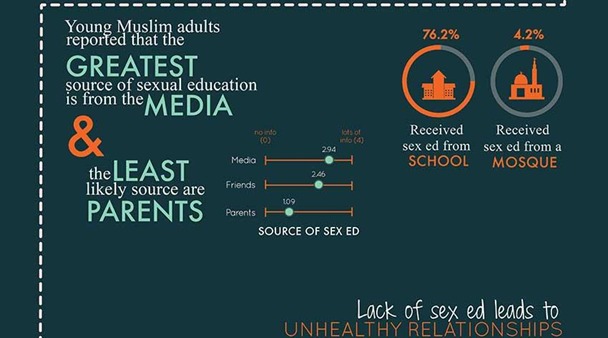

Islamic institutions offer minimal aspects of health education, especially when it comes to sexual health. A survey, conducted in 2014 by Sobia Ali-Faisal, PhD, co-founder, MAC Research: Excavating Truth to Create Cultural Change, University of Windsor, revealed that 4.2% of Muslim youth reported receiving sex education from their mosque, compared to 72.6% in school. Moreover, they reported that their greatest source was the media and their parents were the least likely source of such information. Most Muslim youth living in the West acquire this type of knowledge from secular resources.

The Drawbacks of Secular Health Education

I taught a health class at an Islamic school for several years using a medically accurate, age-appropriate and comprehensive public-school health textbook. However, I found two major drawbacks to using only secular health resources.

Muslim Youth Need Islamic Health Teachings. According to Muslims, religion and science are not mutually exclusive because Islam is congruent with all forms of knowledge, especially health. For example, reproductive and sexual health (e.g., menstruation, puberty, hygiene, nocturnal emissions, intimacy, family planning and consent) is one of the two most heavily discussed topics in Islamic jurisprudence. No other religion even comes close in this regard.

Islamic health education encourages sexual responsibility by:

• Explaining intergender relations, instilling inner and outer modesty, avoiding sexually explicit content, lowering one’s gaze and learning the physical, social, mental and spiritual risks of indulging in casual sex.

• Emphasizing that personal autonomy is based on our bodies being an Amana (trust from God), unlike secular health, which often prioritizes personal autonomy based on self-interest, and addresses cultural stigmas and discrimination (e.g., talking to a mental health professional) and social health issues (e.g., racism and mistreating women).

• Using tazkiya (spiritual purification) to endure personal struggles such as coping with grief, divorce, abuse, body image and personality struggles (e.g., gossiping, anger or envy).

• Addressing Muslim youths’ unique health issues.

A 2016 research study by the Institute of Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) called Meeting the Needs of Muslim Youth: Preventing and Treating Drug Use reports that all youth deal with the same challenges (e.g., sexual desire and substance use). However, Muslim youth have unique issues, among them anti-Islamic sentiment that leads to bullying, discrimination and racial profiling, as well as struggling to understand drug legalization, transgender and other contemporary issues).

ISPU researcher Zeba Iqbal writes “If parents and community leaders wish to help young Muslims make sense of these issues in light of normative Islamic teachings, they must address these topics head-on. Muslim educators are valuable in starting these conversations.” (“Meeting the Needs of Muslim Youth: Preventing and Treating Drug Use,” January 13, 2016).

Health Concepts Don’t Always Align with Islamic Principles. In secular health classes and publications, health topics are often presented as American cultural issues, whereas Islam defines them as moral issues. This includes dating and pre-marital sex; the right to consume alcohol, tobacco, or other substances after a certain age; viewing pornography and “adult material” as an acceptable form of exploration and enjoyment; and putting self-desire and individualism above God.

Additionally, some health topics are presented as social justice issues, such as same-sex attraction and gender dysphoria. Secular health resources promote these discussions as “identities” and as the only acceptable view. Islam has its own understanding, and Islamic health can provide that discussion. Subject-knowledge experts Mobeen Vaid and Waheed Jensen write, “Robust curricula must be developed for the teaching of an Islamic sexual and gender ethic, one that authentically draws on the Islamic legal, ethical, theological, and spiritual traditions … Much of this work has not even started and in other cases remains severely underdeveloped” (“And the Male Is Not like the Female: Sunni Islam and Gender Nonconformity,” Dec. 30, 2020).

Health Challenges

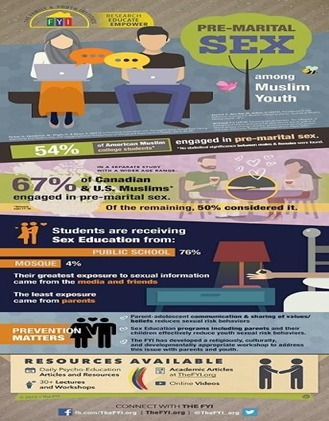

The way health issues are taught to Muslim youth may lead to negative influences and confusion. A 2001 research study by Dr Sameera Ahmed (executive director, The Family & Youth Institute), found that 54% of Muslim American college students have engaged in premarital sex. A 2014 survey by Dr Sobia Ali-Faisal reported that 67% of North American Muslims aged 17-35 have done so as well. Of the remaining, 50% had considered it.

The Family and Youth Institute’s infographic

Ahmed also found that Muslim American college students have consumed alcohol (46.2%), used illicit drugs (24.6%), smoked tobacco products (37.3%) and gambled (30.4%). Similarly, ISPU’s 2020 American Muslim Poll found that 37% of Muslim Americans know a fellow Muslim who is currently or has struggled with alcohol or other drug addictions.

Muslim youth may not only feel enticed to engage in such practices but some are indoctrinated into thinking that Islam is in the wrong or needs to be updated when its principles clash with common secular practices. Some of them even begin to doubt Islam’s truths to the extent that they leave it. A 2015 Pew Research study found that approximately 20% of those raised as Muslim do not identify as Muslim in adulthood.

Just being Muslim or attending an Islamic school isn’t enough. Muslim youth deserve evidence-based answers when asking about the underlying wisdom behind Islamic rulings. To date, no Islamic institutions teach a comprehensive health program with Islamic values. As parents, educators and community members, we must become proactive and encourage Islamic institutions to offer such programs.

Teaching Health with Islam

The Prophet’s (salla Allahu ‘alayhi wa sallam) Companions dealt with the same health issues as do today’s Muslim youth, and he offered them real answers and solutions.

For instance, Zahir bin Haram struggled with his body image. The Prophet built up his confidence by telling him God valued him. He defended Al-Nuayman ibn Amr, who had an alcohol problem, by telling those who cursed him to hate the sin, not the sinner. Even the Prophet struggled during his year-long sadness, occasioned by the deaths of Khadija and Abu Talib, by relying on God and the community for emotional support.

In addition, he taught the young Fadl ibn Al-‘Abbas ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib to take personal responsibility for controlling his sexual urges by lowering his gaze and encouraged Madinan women to have no qualms about their strong personalities and inquisitive minds.

Health education that centres on the Muslim narrative are the basis of my book series, “Islamic Health,” the first of its kind to address our youth’s most common health questions. Written as a preventive intervention — putting the Islamic way of life at the forefront of its answers — it teaches our youth to prioritize their overall well-being, for doing may make them more likely to practice Islam with confidence and thus less likely to engage in risky behaviour.

The series’ first book, “Islamic Health Book I: Ages 9 and Up,” deals with community engagement and rights, puberty, menstruation, hygiene, self-esteem, diet, fitness, bullying, racism, online safety, gaming and other topics. It has been endorsed by The Family & Youth Institute (FYI), the Islamic Schools League of America (ISLA), the Council of Islamic Schools in North America (CISNA) and the Muslim American Society Youth Ministry (MASYM).

Endorsements with Testimonials Photo

The series’ second book, “Islamic Health Book II: Ages 14 and Up,” coves common reproductive illnesses, controlling sexual desire, intoxicants, mental illness, sexual violence, women’s rights, the marital process, genderism, same-sex attraction, controlling one nafs (desires) and more.

Both volumes were content edited by Duaa Haggag (LPC and FYI community educator). Dr Waheed Jensen, a subject-knowledge expert on same-sex attraction and gender dysphoria, content edited those two chapters, and Xhengis Aliu (creative director, The Islamic Medical Association of North America) created the graphics.

“Islamic Health” can be taught in Islamic schools, weekend schools, youth study circles as well as by parents to their children at home. Both books include a teacher walk-through section with pacing guides and chapter planning guides, section activities to fuel thinking and character development, as well as supplemental resources that elaborate upon key concepts. The series will be available in early 2022.

I hope this resource will open the door to having conversations with our youth that will not only put them in the driver’s seat but will also provide them with evidence-based health answers that are appropriate to their continued development as both spiritual and moral beings.

Amber Khan, D.O., is a health educator for Muslim communities. For updates on “Islamic Health,” follow @islamichealthseries on Instagram or contact her at IslamicHealthEducation@gmail.com.