Muslim Americans should understand the cultural and political implications of the Congressional Gold Medal award and other honors

By Irshad Abdal-Haqq

January/February 2023

We honor and preserve our cultural and religious legacies through books, photographs, oral traditions, rituals and our artistic expressions — music, dance, clothing, poetry, paintings and culinary delights. We even convey them through massive monuments fashioned from stone and bronze, perched high upon a pedestal.

But there is another type of monument, one we often disregard. Medals and coins may seem like crude bits of metal that are not worthy of much attention. When carefully examined, however, you may discover that many of them are miniature monuments testifying to remarkable people, historic change and lofty ideals. You may discover that many are precious gems of gold, silver or bronze dedicated to honoring our cultural and religious legacies as effectively just as any other method we use.

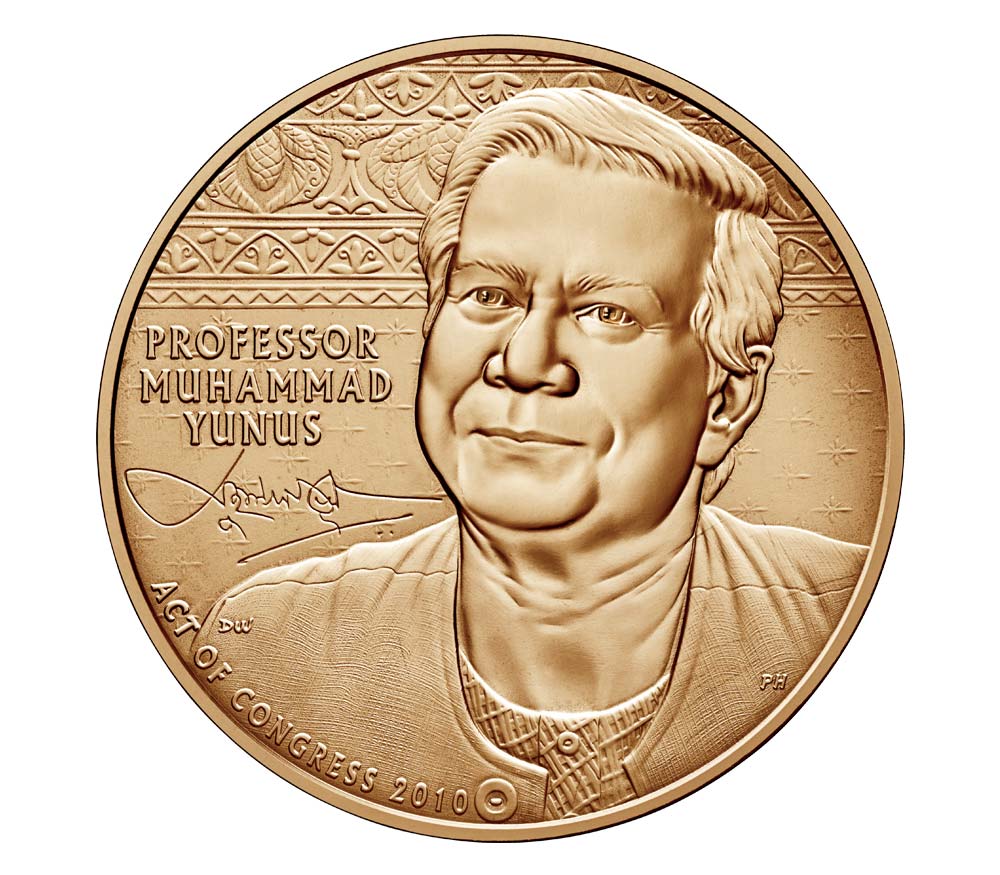

The Congressional Gold Medal bestowed upon Bangladesh native and Grameen Bank founder Muhammad Yunus is a case in point of particular relevance to Muslim Americans. This award is the U.S. Congress’ highest expression of appreciation for achievements and contributions by individuals and institutions. In the case of Yunus, it was in recognition of his contributions to fighting global poverty through the microcredit lending programs he established or inspired throughout the world.

In opening remarks presented during the award ceremony on April 17, 2013, Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) highlighted the fact that it was the first time in history the award was being conferred upon a Muslim. This comment’s significance — greeted with thunderous applause — by a politically astute senator cannot be overstated. It indicates that in Durbin’s mind, who cosponsored the legislation authorizing the award, Yunus represented more than just himself- he represented Muslims. As such, the award honors not only Yunus’ achievements as an individual, but also as a representative of the Muslim community.

For this reason, it behooves Muslim Americans to understand the cultural and political implications of the Congressional Gold Medal award and other honors that may be conferred upon fellow Muslims in the form of medals or their numismatic relative: coins.

Like paper currency and postage stamps, the artistry, imagery and inscriptions on medals and coins tell a story about the civilization that produced them. For thousands of years, societies have honored leaders, historical events and the accomplishments of talented individuals by engravings on their numismatic materials. In this respect, the U.S. is no different. Future historians, anthropologists and archeologists will most certainly study its current medals and coins as they now do those of earlier societies — treating them as pathways through the tunnel of time. There is extensive literature on this concept. See, for example, Amy McKeever’s “What can the faces on its currency tell us about a country?” (National Geographic, March 15, 2021).

Yunus had previously been awarded the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize and a 2009 Presidential Medal of Freedom. Unlike the Congressional Gold Medal, those medals neither display the recipient’s image, nor do they include inscriptions reflecting his/her philosophy. Lastly, the government doesn’t issue duplicates of them for distribution to the public. The Congressional Gold Medal bears Yunus’ image on its front and an inscription quoting him on the back.

Importantly, the law authorizing the award also authorizes the U.S. Mint (the Mint) to issue bronze duplicates for sale to the public as collectibles. In this respect, the 3-inch and 1.5-inch diameter bronze duplicates of the gold medal are like the other commemorative gold, silver and copper clad coins routinely issued by the Mint. Typically, such coins aren’t used in everyday financial transactions but are retained, resold and perhaps displayed by collectors, hobbyists and others with a special interest in the subject matter or message reflected by a particular coin.

Without question, the Yunus bronze duplicate is an appealing work of art. It represents a further breakthrough in the U.S. government’s effort to reflect racial, cultural and gender diversity in its numismatic artistry and legacy. To possess such an emblematic artifact and simply store it away in a dresser drawer or jewelry box would limit its potential in relating the Muslim American story. By displaying and discussing the medal’s significance with our youth and others, however, Muslim Americans can help preserve our collective cultural heritage.

There are several ways to display a medal or coin. It can be preserved in a jewelry box or other container and brought out during family gatherings for viewing and discussion; mounted on a display holder and placed upon a shelf or mantel; or framed and hung upon a wall, accompanied by related illustrations or descriptive statements in a similar manner as the framed El Hajj Malik El Shabazz (Malcolm X) postage stamp collage commissioned by the U.S. Postal Service in 2002. Since the Mint has not commissioned a comparable collage for the Yunus bronze medal, owners would have to compose their own collage or engage an artist to do so.

Obviously, medals and coins honoring a person who happens to be Muslim shouldn’t be embraced indiscriminately. For example, many Muslims wouldn’t give the same consideration to the Congressional Gold Medal awarded to Yunus as to the one authorized posthumously for Anwar Sadat in 2018. Not every medal honoring a Muslim has the same significance for everyone. An individual’s values and political philosophy play an important role in determining whether a government honor is suitable for display within their household or place of business.

Ultimately, however, Muslim Americans probably should embrace the Muhammad Yunus gold medal and bronze duplicates as hallmarks of achievement and inclusion for Muslims in America. Since the Mint’s founding under the Coinage Act of 1792 until the 1980s, with rare exception, the only real-life people appearing on American medals and coins were exclusively powerful or famous men, who also happened to be white and Christian.

Prior to the late 20th century, anyone relying on official American government numismatic materials as indicators of the people and events that mattered would have had received a distorted view of reality. They would have concluded that real-life Muslims, women, African Americans, Native Americans and members of other ethnic groups played only a marginal role, if any, in the evolution of American culture and its democratic principles. Thus, in nearly 200 years of issuing medals and coins, the Yunus medal is the first that even hints at acknowledging the historical presence of Muslims in this country.

The Mint’s issuance of commemorative medals has evolved from a tradition of excluding real-life women and non-whites to embracing a policy of full inclusion. The motivation behind this change is debatable. It may involve a sincere desire for equity in official numismatic creations, but it most certainly also includes a profit motive. As the demographics of the U.S. changed, the Mint realized that its very survival as a sales outlet depends on appealing to a wider customer base (United States Mint 1995 Annual Report, pp. 17-18). But whatever the motive, the outcome has been a cultural and artistic bonanza for women, people of color and others.

In addition to the Yunus medal, other noteworthy examples of numismatic diversity include the 1978 Congressional Gold Medal awarded to the late singer and activist Marian Anderson — the first conferred upon an African American — and its companion bronze duplicate; the 2000 Sacagawea brass one dollar coin, the first depicting a real-life American Indian; and the 2022 Anna May Wong quarter depicting an Asian American on a coin for the very first time in the Mint’s history.

While digital and credit card use will continue to replace paper currency and coins in financial transactions, the Mint’s issuance of commemorative medals and coins in honor of prominent individuals and historic events also will continue. Thus, although the Yunus bronze medal is the Mint’s first to feature a Muslim, many more are sure to follow. And whenever such miniature monuments honor the Muslim community, Muslim Americans should include them among the ways we transmit our legacy.

Irshad Abdal-Haqq is a Washington, D.C.-based author who published “Dash: Young Black Refugee and Migration Stories” in 2021. He is completing a book about African American images on coins and medals, while working on a collection of short stories about the African American Muslim experience.

Tell us what you thought by joining our Facebook community. You can also send comments and story pitches to [email protected]. Islamic Horizons does not publish unsolicited material.